| |

The Ben Franklin Bridge and the Waterfront

<== To a short-cut page to all the photo albums of the bridge

<== To a short-cut page to all the photo albums of the bridge |

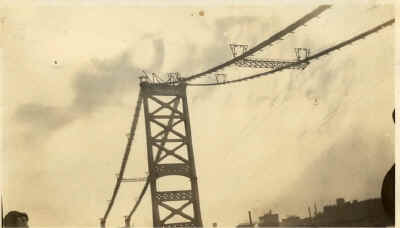

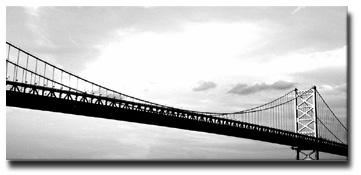

Until the construction of the Ben Franklin Bridge in the early part of the 20th

century, the only way to cross the lower Delaware River was by ferry boat; Walt

Whitman ventured back and forth from industrial Camden this way. But

something more permanent was needed to allow rapid, large-scale river crossing.

Given advances in engineering around the turn of the century, the technology for

a long suspension bridge that would permit river traffic below and car/train traffic above

was now available. All that was left was the need to raise money and to work

between governmental authorities,

so a new agency was born: The Delaware River Bridge Joint Commission (now known

as the Delaware River Port Authority or DRPA). This agency, a cooperative

venture of the states of Pennsylvania and New Jersey and the city of

Philadelphia, began planning the bridge the Delaware River Bridge in 1919. They hired

a local engineering firm led by Polish-born Ralph Modjeski

(1861-1940) and a well known French-born American architect who did considerable work in both

countries, Paul Philippe Cret

(1876-1945), to design the bridge. Modjeski was a renowned engineer who was a

bit of a legend in the bridge business. In addition to the Ben Franklin Bridge

he also was chairman of consulting engineers for the San Francisco-Oakland Bay

Bridge along with about 50 other bridges. Cret was a major exemplar of the Beaux

Arts school or architecture and designed a number of museums, libraries and

monuments as well as more mundane structures such as bridges. Read a

bit about this collaboration and how it was established. And they were certainly thinking

big: the plan was for the world's longest suspension bridge at a cost of

$40,000,000.

Construction was begun in 1922, and the bridge was opened to vehicular

traffic in 1926. To the right are some photographs courtesy of (and copyright

by) the Atwater Kent Museum in

Philadelphia that show the bridge in the 1930s. While the original plan for the bridge called for the

demolition of St. George's Church, the oldest Methodist church in the United

States, a lawsuit resulted in the relocation of the bridge and a modest 14 foot

space between the church and the Philadelphia base of the bridge. You can see

the church in the upper picture. It's the one without the steeple. As the bridge

was preparing to open, there was a debate about whether or not to charge tolls.

It might be surprising to know that only the New Jersey authorities wanted to collect

tolls until their investment in the bridge was recouped. In a compromise, the

Pennsylvania and Philadelphia delegates agreed to tolls to prevent a lengthy

court battle (this case had already to  gone to the US Supreme Court) and to open

the bridge on time. One reason for getting it opened by then was to allow people

to visit the City of Philadelphia's somewhat unsuccessful Sesqui-Centennial

celebration of the constitution. The official opening was July 1, 1926 where a

quarter-million pedestrians enjoyed the bridge before cars were allowed to cross

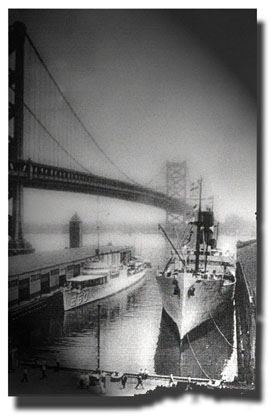

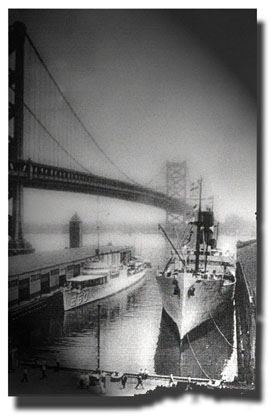

at midnight. The Bridge served the bustling waterfront district of

Philadelphia and even replaced some piers used for shipping. The early 20th century saw the construction of large piers and

these were instrumental in maintaining domestic and international trade through

the ports of Philadelphia and Camden. Two drawings from the Independence Seaport

Museum (shown under Bridge Pictures below) show these engineering marvels of 100 years ago. Many of these piers are

still being used... some for their original purposes and some for housing.

The tragic accident at Pier 34 illustrates some of the problems with building using

timbers stuck deep into river mud. It is quite miraculous that with meticulous

care these piers can still support heavy duty activities to this day. In

the photo to the left you can see large ships berthed at Piers 9 and 11 just

south of the Ben Franklin

Bridge. These piers are about 500 feet in length and

can easily accommodate ocean going vessels. One reason for building a bridge of

this height was to permit the passage of large ships further up river to the

bustling piers to the north. The picture below gives you an idea of how large

the vessels are that go under the bridge. gone to the US Supreme Court) and to open

the bridge on time. One reason for getting it opened by then was to allow people

to visit the City of Philadelphia's somewhat unsuccessful Sesqui-Centennial

celebration of the constitution. The official opening was July 1, 1926 where a

quarter-million pedestrians enjoyed the bridge before cars were allowed to cross

at midnight. The Bridge served the bustling waterfront district of

Philadelphia and even replaced some piers used for shipping. The early 20th century saw the construction of large piers and

these were instrumental in maintaining domestic and international trade through

the ports of Philadelphia and Camden. Two drawings from the Independence Seaport

Museum (shown under Bridge Pictures below) show these engineering marvels of 100 years ago. Many of these piers are

still being used... some for their original purposes and some for housing.

The tragic accident at Pier 34 illustrates some of the problems with building using

timbers stuck deep into river mud. It is quite miraculous that with meticulous

care these piers can still support heavy duty activities to this day. In

the photo to the left you can see large ships berthed at Piers 9 and 11 just

south of the Ben Franklin

Bridge. These piers are about 500 feet in length and

can easily accommodate ocean going vessels. One reason for building a bridge of

this height was to permit the passage of large ships further up river to the

bustling piers to the north. The picture below gives you an idea of how large

the vessels are that go under the bridge.

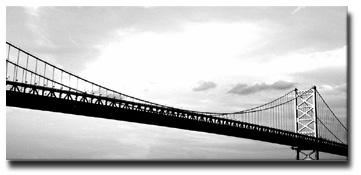

The bridge was re-named for Benjamin Franklin in 1956. Its blue color allows it to stand out from

other bridges and creates a striking vista by day. In 1987, as part of the celebration of the bicentennial

of the Constitution, a privately funding lighting scheme for the bridge was

implemented. It is no exaggeration to say that this bridge lighting project was

the key to the redevelopment of the waterfront. Turning a simple bridge into a

kinetic light sculpture generated a buzz that made restaurants and nightclubs

seem like a natural extension. The lighting was designed by the architectural firm of Venturi Scott-Brown

and consisted of bright lights aimed at the cables of the bridge. After dark the

lights come on and the cables glow an ethereal whitish-blue color. At intervals the

lights flash off and on giving a sinuous quality to the bridge. Initially the

lights were synchronized with the passage of PATCO trains, but the current

schema is much more fluid and there is no discernible pattern to the flashing

lights. During the repainting of the cables the lights were off much of the

time, but they're back now. On cloudy nights there are 2 bands of light in the

sky above

the bridge which can be quite an interesting effect. The bridge was re-named for Benjamin Franklin in 1956. Its blue color allows it to stand out from

other bridges and creates a striking vista by day. In 1987, as part of the celebration of the bicentennial

of the Constitution, a privately funding lighting scheme for the bridge was

implemented. It is no exaggeration to say that this bridge lighting project was

the key to the redevelopment of the waterfront. Turning a simple bridge into a

kinetic light sculpture generated a buzz that made restaurants and nightclubs

seem like a natural extension. The lighting was designed by the architectural firm of Venturi Scott-Brown

and consisted of bright lights aimed at the cables of the bridge. After dark the

lights come on and the cables glow an ethereal whitish-blue color. At intervals the

lights flash off and on giving a sinuous quality to the bridge. Initially the

lights were synchronized with the passage of PATCO trains, but the current

schema is much more fluid and there is no discernible pattern to the flashing

lights. During the repainting of the cables the lights were off much of the

time, but they're back now. On cloudy nights there are 2 bands of light in the

sky above

the bridge which can be quite an interesting effect.

| A new lighting

scheme for the bridge has been added. In addition to the old lights shining

from above the roadway directly upward to the cable, there

are 4 new features. The anchorages have

been illuminated as have the towers. There is a row of lights along the span itself (red, white

and blue here, but changeable) and white lights along the pedestrian span on

both sides. This lighting effect modification is quite dramatic.

The rendition to the right is what I call tutti-frutti with a rainbow of lights on the towers. Despite the rusting steel

and the peeling paint, the bridge at night can look really magical. This

photograph has been "Photoshopped" a bit to bring out the colors

in a more painterly way, but it is really this colorful. |

|

In addition to seven lanes of motor traffic, the bridge

has a high speed urban rail line on either side as well as a walk/bike way.

While Interstate 676 feeds into the bridge at both ends, the actual structure is

not quite up to interstate highway standards. So for now, the bridge is still US

Highway 30. In any event, the bridge

gives us a great way to get to Camden (below). In the photo below you can see

the Camden waterfront including the Rutgers campus, the Aquarium and the

Entertainment Center. The USS New Jersey is now also docked in Camden and is open for tours.

|

The bridge is always under some form of repair or

maintenance. Though oddly the project seems to have come to a halt in the past

year with the span west of the Philadelphia anchorage rusting and brooding.

|

|

|

|

From the Philadelphia Inquirer magazine

section, June 14, 2001, the quote below:

"During the first year, the bridge took in more than $2 million;

over that summer, extra toll collectors caught money in paper bags to help

move the lines along.

Most vehicles were charged a quarter. A pedestrian leading a horse,

mule, cow, hog or sheep had to pay 20 cents to cross. If you rode your

horse, it was only 15 cents. Bicyclists paid a dime."

The

bridge is celebrated its 75th anniversary on July 1, 2001. Click on the

banner to learn about the festivities. The

bridge is celebrated its 75th anniversary on July 1, 2001. Click on the

banner to learn about the festivities.

Does

this bridge have stats? You bet! It is currently about the 34th longest

suspension bridge in the world. Below are figures that might mean

something to you.

|

|

Look

at the fireworks and some of the scenes of the anniversary party by

clicking below Look

at the fireworks and some of the scenes of the anniversary party by

clicking below

|

|

Bridge Links  |

Moods of the Bridge

Click on the image above to see

the bridge express its different moods; click to the right to see what

passes under the bridge. |

Bridge statistics

- Total length of bridge: 9,650 feet

- From anchorage to anchorage: 3,536

- Length of main span: 1,750

- Width of bridge: 128 feet

- Width of roadway: 57 feet originally

planned, but now includes 2 lanes initially planned for streetcars and is 78

feet for 7 lanes of traffic

- Height of towers: 380 feet

- Clearance above mean high water: 135 feet

- Diameter of cables: 30 inches

- Number of wires in each cable: 18,666

- Ultimate strength of cables: 125,000 tons

- Weight main span per linear foot: 26,000 pounds

- Live load capacity per linear foot: 12,000 pounds

- Weight of steel towers: 10,000 tons

- Cables and suspenders: 7,350 tons

- Suspended spans: 18600 tons

- Anchors: 6,000 tons

- Approaches: 25,800 tons

- Cars crossing per day: 100,000

Masonry

* Pictures not

otherwise noted are copyright Tom Fekete, 2000,

2001, 2002, 2203, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007

|

gone to the US Supreme Court) and to open

the bridge on time. One reason for getting it opened by then was to allow people

to visit the City of Philadelphia's somewhat unsuccessful

gone to the US Supreme Court) and to open

the bridge on time. One reason for getting it opened by then was to allow people

to visit the City of Philadelphia's somewhat unsuccessful